In this article, stress means when our bodies speed up, or physiological stress. Things that cause stress, for example financial worries or problems in relationships, are called stressors.

Stress is generally seen as something negative that we need to eliminate from our lives, but it actually also has an important function. Our bodies need a certain amount of stress for any kind of change, growth or development. Understanding how stress can actually be helpful can have a positive impact on how you deal with it, whereas focusing only on the dangers of stress can make you feel even more stressed than before (see footnote).

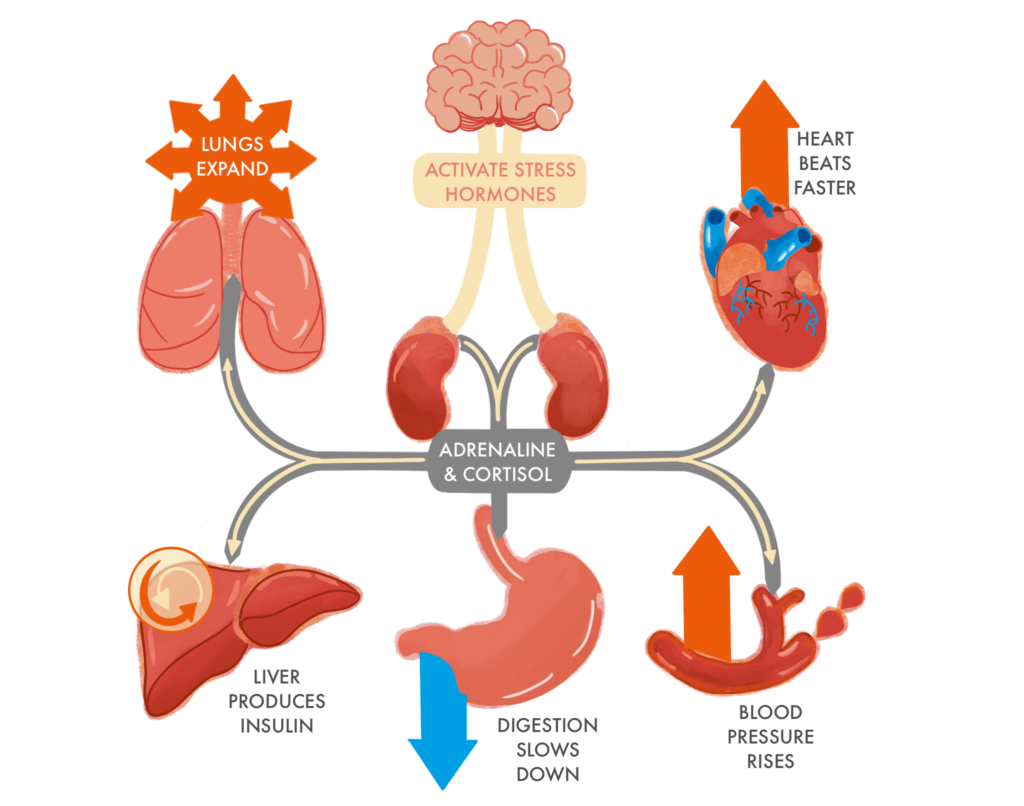

STRESS PREPARES YOUR BODY FOR ACTION

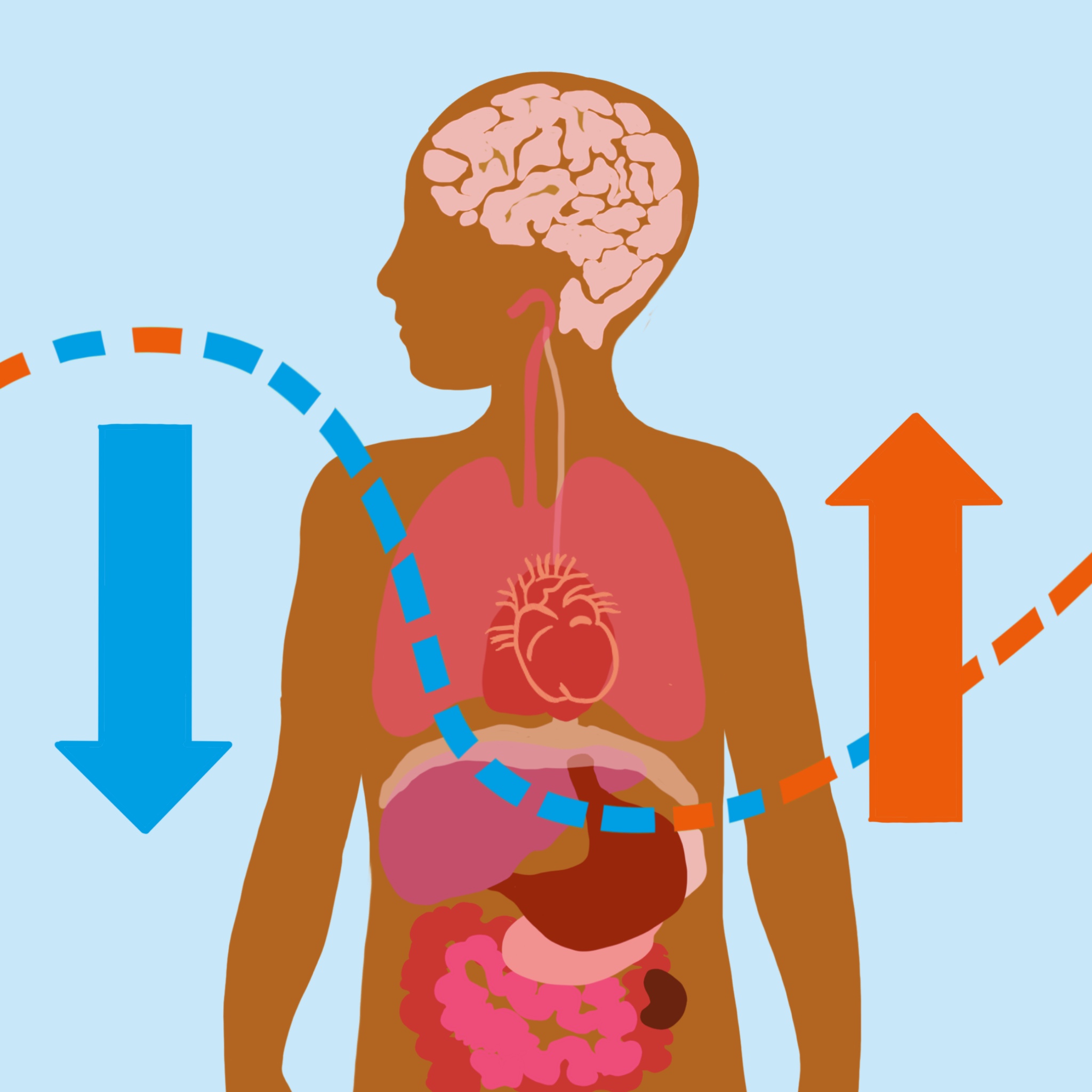

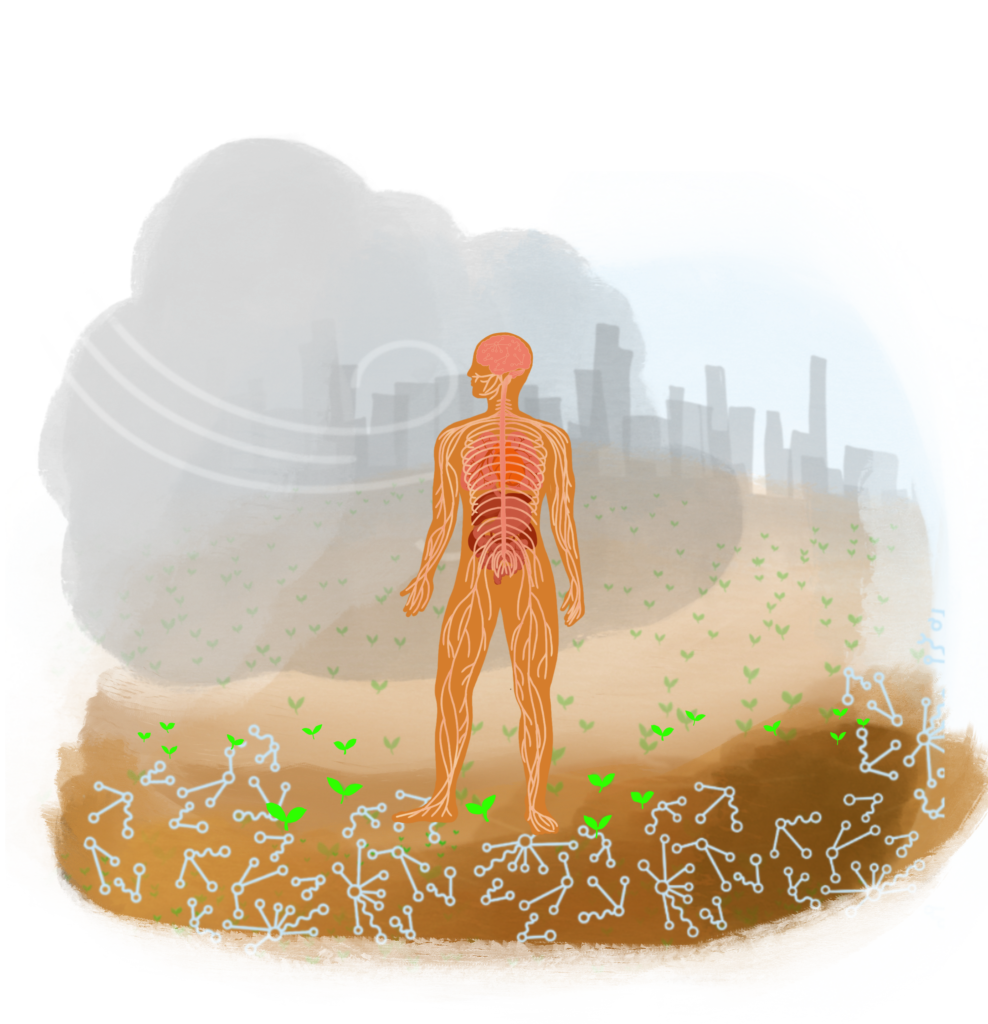

Our bodies have a natural capacity to regulate stress. Regulation means speeding up or slowing down to adapt to whatever is going on inside or around us.

Understanding how your autonomic nervous system works can help you identify and use this ability to care for yourself and others.

PHYSIOLOGICAL STRESS CAN FEEL GOOD

Stress works like a “GO-signal” in our bodies that helps us learn and adapt to our environment. When your body speeds up, two windows of opportunity open:

ALERTNESS

It’s easier to take in new information when we’re alert than when we’re too calm. When you enter a building for the first time, you’re usually more alert than when you enter your home.

INTENSITY

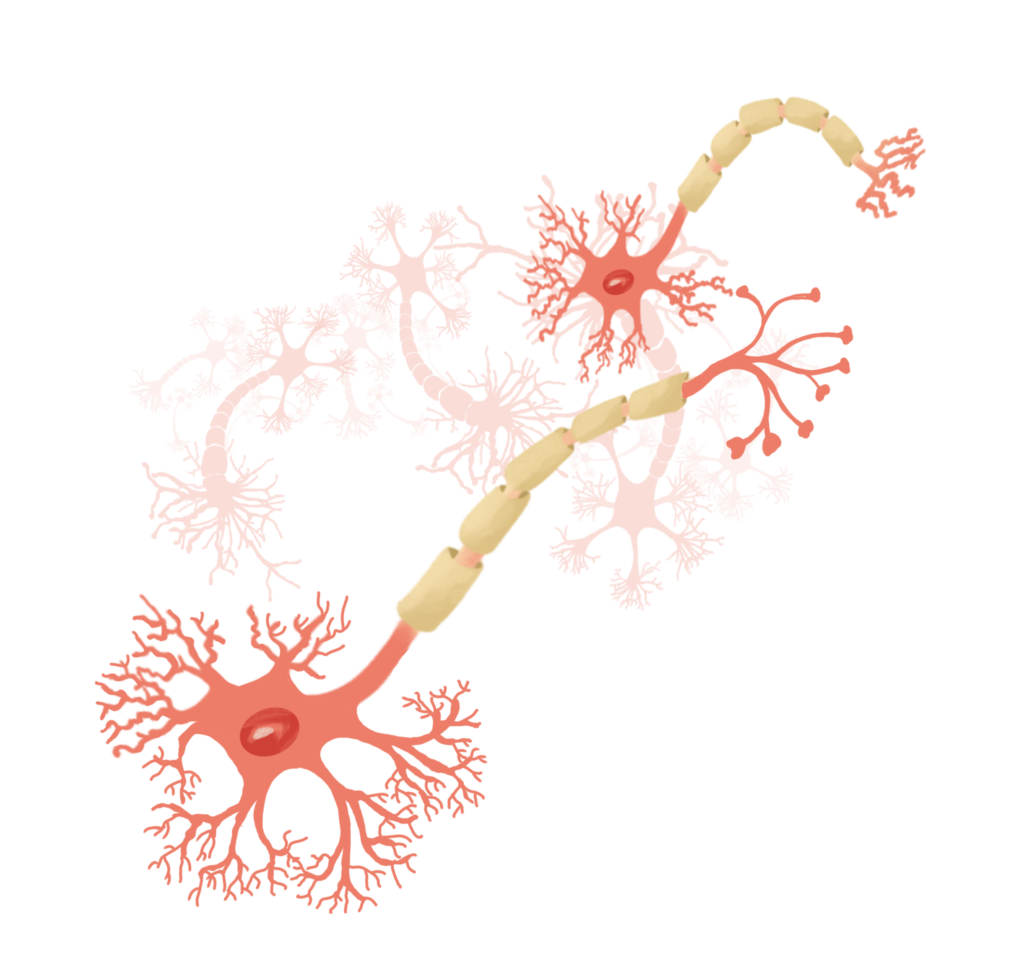

In a GO state, stress hormones help our nerve cells form new networks. Networks between nerve cells help us recall new information and skills in the future.

Think of the rush that you get when you hear really exciting, positive news. On a physical level, that rush looks pretty much the same as fear: your heart races, your temperature rises and your muscles are ready for action.

On a physical level, excitement can feel (and look) just like fear.

TOOL: Use stress for good

Can you remember the last time you took a test, spoke to a large group of strangers or needed to get a tough physical job done quickly? Remember how you felt. Depending on the situation, you may have felt excited and energised, or anxious or irritated. Next time you’re in a similar, mildly stressful situation, try this:

- Notice how your body speeds up

- Remind yourself that this is making you more alert, more energised and more able to tackle the test at hand.

- Notice WHAT FEELING ENERGIZED FEELS LIKE in your body: is it pleasant, unpleasant or neutral?

- If it’s pleasant or neutral, try to appreciate how your is body rising to the challenge!

HOW MUCH STRESS DO YOU NEED?

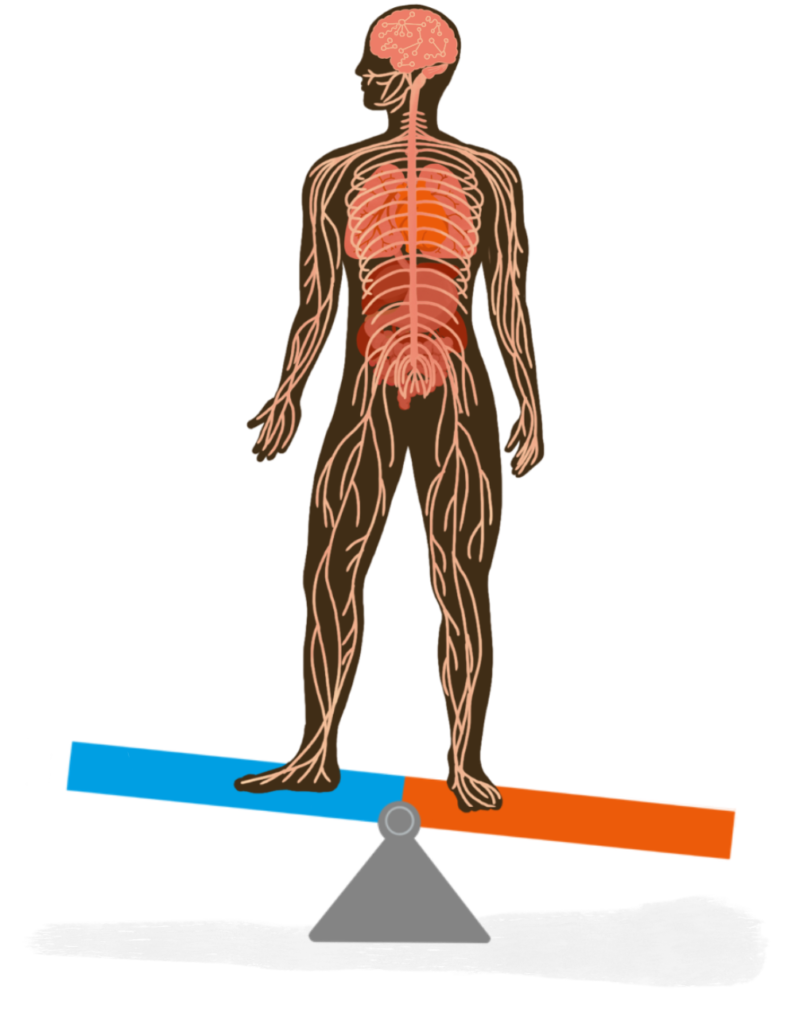

Too much stress can overload our nervous system’s natural ability to keep a healthy balance between activation and recovery. Even if we’re not aware of it, managing stress-overload costs our bodies a lot of energy and can have a negative impact on our wellbeing – including how well or poorly our social interactions with other people go.

Too little stress, on the other hand, isn’t good either. Imagine, for example, never getting irritated enough to change things in our lives that cause stress. Stressful emotions make us aware of problems we need to take care of.

A certain amount of stress is beneficial:

- Stress gives our bodies the signal that something needs to change, opening biochemical “windows of opportunity” that help us learn and adapt.

- Stress is, at the most basic level, what makes us MOVE. Without any stress in our lives, we have no need for development or change.

- Acute, short-term stress that lasts for minutes or hours has actually been proven to protect us from infection by speeding up our internal immune responses (see footnote).

In this sense, managing stress doesn’t mean eliminating it from our lives. It’s about HOW MUCH and for HOW LONG, and can mean both finding calm and getting energized, depending on the challenge at hand.

WHEN STRESS FEELS BAD

Over time, too much stress can lead to “distress signals”, for example unpleasant physical aches and pains, feelings and thoughts. These differ from person to person and are not a sign of weakness. They’re signs that it’s time to make a change.

Long-term stress-overload:

In our social lives: withdrawing from friends and family, “clinging” to others or frequent conflicts.

In our bodies: unpleasant tension, sleeping and digestive problems, frequent headaches, irritability and fatigue.

In our feelings: feeling “empty” or “heavy-hearted”, angry outbursts or uncontrollable rage.

In our minds: “thinking too much”, having unpleasant thoughts that keep popping up, or intense negative thoughts about ourselves and others.

Short-term stress:

In our social lives: temporary loss or increase in compassion, interest and patience with others.

In our bodies: feeling “ready to go”, tense, highly alert, impulsive and strong – can be pleasant or unpleasant!

In our feelings: excitement, overwhelming joy, sadness, anger, disgust, …

In our minds: decisiveness, focus, but also “tunnel vision”. Temporary loss of the ability to keep others hearts and minds in mind.

DEALING WITH SHORT-TERM STRESS

Remember: stress doesn’t just happen in our minds. Our bodies have a natural capacity to regulate stress. You can kick-start this ability with simple TOOLS that target your autonomic nervous system, for example by using all of your strength to push against a wall, and exhaling when you release.

DEALING WITH LONG-TERM STRESS

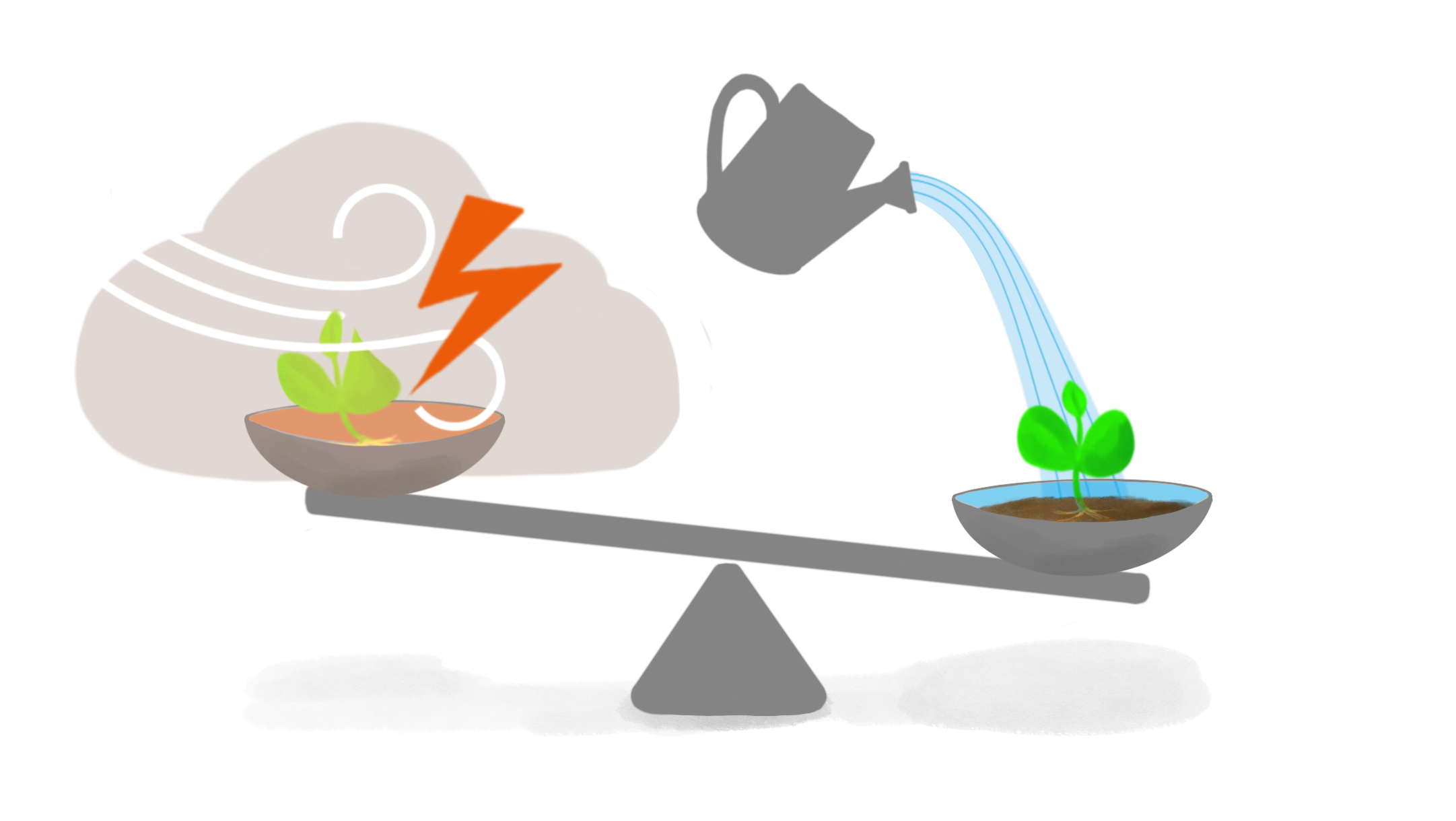

When we’re facing many stressors, short-term strategies like the above are only part of the solution. Stress-overload costs your body a lot of energy. Imagine this like as a see-saw:

The more stress you have to deal with, the more important it becomes to replenish what gives you strength.

CARE FOR WELLBEING LIKE A GARDEN

It’s easy to put off caring for ourselves. When we’re distressed, taking time to rest and recharge can feel like an additional, time-consuming burden. This is part of human nature: under stress, our focus is drawn to short-term, immediate solutions. While immediate responses are often necessary, sustainable wellbeing is like caring for a garden: the sooner you respond to distress signals, the higher the payoff.

Imagine you’re growing a garden with fruits and vegetables that sustain you throughout the year. When pests, a storm or drought come along, the longer you put off caring for your garden, the less you’ll be able to harvest. The same goes for wellbeing. Caring for your wellbeing is the key to securing a harvest that nourishes you throughout stressful times.

SOURCES:

Crum, A., Salovey, P. & Achor, S. Rethinking stress: the role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2013 Apr; 104(4):716-33. doi: 10.1037/a0031201. Epub 2013 Feb 25. This study with adults in a corporate setting showed that stress management training that emphasised the negative effects of stress led to participants experiencing more stress than before the training.

Dhabhar, F.S. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol Res 58, 193–210 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0. This study showed how a certain amount of stress enhanced immune responses during